The Christopher Goodhand family of Kent and Queen Anne’s County, Maryland were wealthy landowners, farmers, and enslavers originating in England. Christopher Goodhand born 1650, in Lincolnshire, England, arrived on Kent Island in the late 1660s as an indentured servant. He served his contract and received a land grant. His family and descendants are well-documented on Kent Island in the Chesapeake Bay. Goodhands later settled in the Sudlersville area between Dudley Corners and Crumpton on the Chester River.

Christopher Goodhand’s brother Capt. Marmaduke Goodhand commanded the Speedwell, and made at least three voyages to Senegambia to purchase African slaves and take them to the colonies. According to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, the voyages occurred annually from 1865 to 1688.

The first voyage was recorded in the Royal African Records simply as to provide 200 negros and discharge in Maryland, but all three voyages may have been to provide captive Africans for three planters, Edward Porteus, Christopher Robinson, and Richard Gardiner of Maryland and Virginia, working through an agent Jeffrey Jeffeys. In January 1685, the Royal African Company and the Earl of Berkeley commissioned Capt. Goodhand to “sett Sail out of the River of Thames wth yo’r Shipp the Speedwell and make the best of Your way to James Island in the River of Gambia…”

Capt. Goodhand’s journey began in London on January 12 in 1686. The Speedwell arrived in March in Senegambia where the Captain negotiated for and purchased 217 out of the 250 planned Africans. The enslaved boarded and departed on June 6th and spent two months at sea, arrived in Maryland in August. Of the 217 enslaved that, only 192 disembarked. About 81% were men, 17% women, around 3% were children.

James Island’s in the river Gambia is now called Kuntah Kinte Island in the Republic of Gambia. The three square-mile island is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its role in the Dutch and British slave trade. The area was ruled by the Mali empire for several centuries, known for the ruler Mansa Musa. The Songhai empire controlled the area up until the 16th century when it was driven upstream by war with the Portugese.

The second voyage followed a similar schedule, disembarking 221 African Captives on the York River of Virginia in 1867 to Jeffrey Jeffreys on behalf of Christopher Robinson, William Churchill and Dudley Diggs. Of the last voyage, only 206 of 233 captives survived the same journey from Gambia to Virginia.

The same ship may have also transported 170 captive Africans to Barbados from Mozambique in 1682.

Only in 1685 did a serious slave trade to Maryland tentatively begin: in that year, instructions from the RAC’s Committee on Shipping (the ever-active Lord Berkeley was on it) asked a sea captain, Marmaduke Goodhand, to deliver two hundred slaves to be shared among Edward Porteus (a merchant of Gloucester County, Virginia), Richard Gardiner, and Christopher Robinson (a future secretary of the colony), on the Potomac River. Next year, there was a reference to a consignment of “slaves and sugar” in Maryland from Barbados. The intention had been to load

Erenow.com, Lawful to Set to Sea, Chapter 11tobacco, as if the transaction were normal; and there are some other isolated references to slaves arriving at Annapolis or smaller ports onChesapeake Bay.

At the age of 39, Capt. Goodhand fell ill and died in October 1688 in Shadwell Middlesex, near the docks of the Thames (now in London) where he left a will leaving his home and estate mostly to his family and wife Susana Browne. His will doesn’t mention his life as a mariner and slavetrader.

EMORY CHASE – FREE

The Emory Chase family of Queen Anne County begins as a family of free blacks and enslaved in Kent County in the 1830s. Some of my eldest ancestors on the Upper Shore, the Chases were both free and enslaved by the Goodhand family up to and through the Civil War. While there is no documentation to indicate the Chases descended from one of Capt. Goodhand’s cargo of captive African and perhaps Gambian slaves, DNA research does indicate my own family has very deep ethnic roots in the Senegambia region.

Emory Chase Sr. first appears on the written record in the 1832 Free African-American Census of Maryland in Kent County.

“Emory Chase, 28”

The census was taken in response to the growing population of free blacks living in Maryland. There are no other Chases in the immediate vicinity of Emory’s name on the list.

Among the legislative actions of the Maryland General Assembly of 1831 was the passage of “an act relating to the People of Color in this state…The primary intent of the act was to achieve the removal of free African Americans from the state of Maryland in their entirety, sending free blacks to the colony of Liberia.”

The state undertook the census to enumerate the free black population. In some counties, free men were asked directly if they would remove themselves to Liberia. The Maryland Colonization Society which led the local effort was founded in part as a response to the threat of slave rebellion (Nat Turner’s uprising in Virginia was in 1831). The Society saw colonization as a remedy for slavery.

“In 1832 the legislature placed new restrictions on the liberty of free blacks, in order to encourage emigration. They were not permitted to vote, serve on juries, or hold public office. Unemployed ex-slaves without visible means of support could be re-enslaved at the discretion of local sheriffs. By this means the supporters of colonization hoped to encourage free blacks to leave the state.”

Four generations later, the great-great-grandson of the original scion of the family, Christopher Goodhand b.1787, was dying around 1857 on his plantation southeast of Crumpton and near Sudlersville, Maryland. He had served as a Private in the 38th Regiment, Wright’s Militia during the War of 1812, a state delegate, a farmer and hotel owner. By 1850 he had at least five children (Hiram, Josephine, Eugenia, Martha, and Samuel), was married to Susan Pope Sturgess of Baltimore County, and had an estate worth $16,000 according to the Census. According to the US Federal Slave Schedule he owned 10 slaves of various ages by 1850.

- 25, female

- 22, male

- 18, male

- 17, male

- 14, male

- 13, male

- 21, female

- 6, female

- 4, male

- 8 months, male

Several enslaved individuals appear in the inventory of the will of Christopher Goodhand. Remarkably, his will provided for gradual freedom to all of his enslaved, which numbered 11 by then.

This is my last will and testament, that the following named negroes shall be outfitted to their freedom at the time as specified –

Negro woman Maria to be free 1st January 1859

Negro woman Harriet to be free 1st January 1864

Negro girl Amanda to be free 1st January 1873

Negro woman Mary to be free 1st January 1879

Negro woman Mary Ann to be free 1st January 1882

Negro man Richard to be free 1st January 1862

Negro man Emory to be free 1st January 1868

Negro boy Henry to be free 1st January 1870

Negro boy Levi to be free 1st January 1872

Negro boy James to be free 1st January 1882

Negro boy William Emory to be free 1st January 1890

Will of Christopher Goodhand, 1857, Maryland State Archives.

The manumission dates appear to point to the age of the enslaved. The later the date, the younger the enslaved. Goodhand indicated his wife should take a third of the enslaved and the rest be divided by his heirs.

The Emory Chase Snr. family appear in the 1850 and 1860 census reserved for freemen. However, some of his presumed children or nieces/nephews also appear in Christopher Goodhand’s will probated in 1857. The Chase Snr. family group in the 1850 census includes:

- Emory Chase, 40

- Charlotte, 40

- Mary Jane, 8

- Addison, 6

By 1850, Emory Chase Snr. is a blacksmith. The Chase Snr. family group in the 1860 census includes:

- Emory Chase, 60

- Charlotte, 55

- John, 21

- Mary Jane, 18

- Addison, 16

By 1860, Emory Chase Sr. is a farmer with a personal estate worth $400. The Chase Snr. family group in the 1870 census includes:

- Emory Chase, 65

- Charlotte, 64

- Levi, 29

- Emory Jr., 32 (Jr. my addition)

- Addison, 24

A FAMILY FREE AND ENSLAVED

By 1870, Emory Snr. is still farming with $1100 in real estate and $300 in his personal estate. Among the listed enslaved in Christopher Goodhand’s will, my own confirmed ancestors from this group include Emory Chase Jr., Harriet Ann Chase, and Levi Chase. It is also plausible Mary is also my ancestor Mary Jane Chase, another daughter or niece of Emory Chase Snr. Perhaps Maria, to be manumitted the earliest via the Goodhand will, was a sister of Emory Chase Snr.? After emancipation, Richard Chase appears in Sudlersville on the draft registration record for 1863, less than a year after his manumission. Richard and other members of the family group appear in the county, but it’s not possible to determine their exact relationship.

At first, I was really confused as to how several chase family members could appear in the 1850 and then it occurred to me that you simply can not assume that just because a black family appears in a pre-1870 census that the ENTIRE family is free. Slavery fell from the mother and

Levi and Emory Jr. join the household of Emory Chase Sr. by 1870 according to the census. While Harriet never appears in the Chase Sr. household (she is married to neighbor James Milbourne by 1850), her younger brother John who is living with her in 1850 according to the census appears in the Chase Sr. household in 1860 (she is likely still enslaved but married). Later death records of Milbourne children identify Harriet as “Harriet Ann Chase.”

Sadly, the executor of the Goodhand will, Lemuel Roberts notes during the probate, “Boy, William Emory, mentioned in the will has died since the will was made.” William Emory was likely a Chase relation, perhaps Harriet or Maria’s son. By the time of the probate of Christopher Goodhand’s will, a young girl “Sarah” is also

It isn’t clear why Christopher Goodhand, who died by 1857, set out to emancipate his slaves gradually according to his will. They were a considerable part of the wealth of his estate. The probate inventory appraised the enslaved at over $6000. Perhaps the Goodhand family

Christopher Goodhand’s executors – wife Susan Pope Goodhand b.1812 nee’ Sturgis, son Hiram Goodhand, and Col. Lemuel Roberts (a neighbor, farmer, friend, slaveholder, and co-delegate to several State and Congressional conventions) followed the will’s instruction, as they did split up the enslaved. Levi was given to Samuel Goodhand (son of Christopher Goodhand) to “serve 15 years.” Emory Jr. was to serve Susan for 11 years before being emancipated.

FREE TO FIGHT

Susan Goodhand, widowed, eventually emancipated Levi Chase, my 3rd great-uncle during the Civil War –but for a fee.

“Whereas my slave Levi Chase has enlisted in the service of the United States now in consideration thereof I, Susan P. Goodhand, guar Samuel S. Goodhand of Queen Anne’s County, State of Maryland do hereby in consideration of said enlistment, manumit, set free, and release the above named Levi Chase from all service due me; his freedom to commence from the date of his enlistment as aforesaid in the Regiment of Colored Troops in the service of the United States.”

Manumission of Levi Chase, Queen Anne’s County Land Records, Maryland State Archives.

Goodhand took advantage of an offer from the War Department and offered Levi Chase to the US Army for a bounty and filed manumission for Levi in September 1864.

“To facilitate recruiting in the states of Maryland, Missouri, Tennessee, and eventually Kentucky, the War Department issued General Order No. 329 on October 3, 1863. Section 6 of the order stated that if any citizen should offer his or her slave for enlistment into the military service, that person would, “if such slave be accepted, receive from the recruiting officer a certificate thereof, and become entitled to compensation for the service or labor of said slave, not exceeding the sum of three hundred dollars, upon filing a valid deed of manumission and of release, and making satisfactory proof of title.”

Civil War Soldiers, Union, Colored Troops 56th – 138th Infantry Fold3.

Records indicate she was paid $100 bounty after the war. The remaining enslaved Chases were freed when slavery officially ended in Maryland on November 1, 1864 after the Maryland General Assembly wrote a new constitution for the state that made slavery illegal upon that date. Thankfully, the Chases did not have to wait for freedom long.

Private Levi Chase served in the United States Colored Troops in Company I of the 39th Regiment until the end of the war. According to rolls he mustered in March 31st, 1864 in Baltimore. The 39th U.S. Colored Infantry was organized in Baltimore, Maryland beginning March 22, 1864 for three-year service under the command of Colonel Ozora P. Stearns. The 39th participated in several battles including the Siege of Petersburg and Richmond, and the infamous Battle of the Crater in Richmond, VA.

The Battle of the Crater, part of the Siege of Petersburg, took place on July 30, 1864, between the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Robert E. Lee, and the Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade (under the direct supervision of the general-in-chief, Lt. Gen.Ulysses S. Grant).

On July 30, Union forces exploded an 8,000 pound mine to blow a gap in the Confederate defenses. Less seasoned white troops were sent in after the explosion and cut down. Colored units were sent in to save them and further massacred while in a poor position. The attack was a failure resulting in thousands of Union casualties. The Confederates launched several counterattacks. The breach was sealed off, and Union forces were repulsed with severe casualties. The siege lasted another eight months.

Levi’s regiment also participated in the bombardment of Fort Fisher in North Carolina, and its capture, the capture of Wilmington, and the surrender of Confederate General Johnston and his army. The 39th U.S. Colored Infantry mustered out of service on December 4,

MOSS TRACT

In 1869, Susan Goodhand, three years after the close of the war, daughter Martha Sudler nee’ Goodhand, and Susan’s son-in-law J. Morling Sudler, later sold land known as “the Moss Tract” to Emory Chase Snr., Emory Chase Jr., and Levi Chase, and to son-in-law John Jeffers (husband of Mary Jane Chase). Moss Tract directly adjoined the lands of Lemuel Roberts and James Dudley according to the deed. Emory Chase Snr. acquired two fifths and other purchasers –the remaining three fifths. The father and son relationship between Emory Chase Senior and

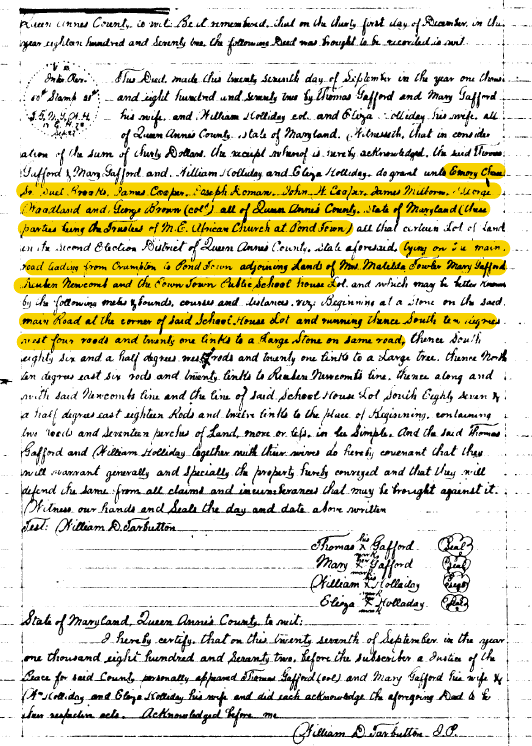

In freedom, the Chase family along with the other formerly free black families they married in to (Doman, Jeffers, Johnson, and Milbourne families) were active members of their community, farming and educating their children, building schools and churches. In 1872, Emory Chase Sr., my 4th great-grandfather, and several other “trustees” including my 3rd great-grandfather James Milbourne, purchased land to found an African Methodist Church, later known as Mt. Pleasant United Methodist Church in Pondtown, just northwest of Sudlersville. The trustees purchased land from the Gafford and Holliday families (African Americans), “being on the main road leading from Crumpton to Pondtown, adjoining lands…and the Pondtown Public School House.” The deed was testified to by William Tarbutton, on whose land both Christopher Goodhand and Lemuel Roberts are buried. None of the Chases have headstones at Mt. Pleasant UM Church. The search goes on for their burial place.

Levi Chase was my 3rd great-uncle by marriage and blood, as he married my 3rd great-aunt, Sarah “Sally” Johnson born 1850 to Asbury Johnson, my 3rd great-grandfather. The marriage took place in Pondtown between 1870 and 1880.

I am the great-great-grandson of Sally’s brother Walter “Wallis” Johnson. Furthermore, Walter Johnson married Sara Catherine Milbourn between 1870 and 1880 in Pondtown. Sarah “Katie” Milbourn was the daughter of Harriet Ann Chase and James Milbourn, my 3rd great-grandparents, and granddaughter of Emory Chase Snr.

Walter Johnson’s father and uncle, Asbury

Asbury Johnson’s 1866 will, just one year after the Civil War ends, shows he was an industrious farmer with dozens of farming tools, cows and horses. But he also owned items that suggested his eyes were on the horizon. He owned a looking glass, 3 pictures, and a clock. He wasn’t rich, but he was free and able to leave an inheritance that included money to each of his seven children and wife.

Asbury and Albert both had Certificates of Freedom signed by Col. Lemuel Roberts in 1857, Christopher Goodhand’s estate executor. Roberts attests to the fact that they were “born free.” In 1805 the Maryland General Assembly passed a law to identify free African Americans and to control the availability of freedom papers. As the lawmakers explained: “great mischiefs have arisen from slaves coming into possession of certificates of free Negroes, by running away and passing as free under the faith of such certificates“. The law required African Americans who were born free to record proof of their freedom in the county court. The court would then issue them a certificate of freedom. If the black person had been manumitted, the court clerk or register of wills would look up the manumitting document before issuing a certificate of freedom. It is plausible Asbury’s father or mother was enslaved by Col. Roberts though I have no documentation yet. The Roberts family connection to the Johnson and Chase family is palpable and leaves much to be explored.

Susan Goodhand passed away in 1877, about 10 years after her last documented contact with the Chase family.

*Update – for more on the Johnson family, see Johnson Roots on Comegys Reserve.

Sources.

- “Maddison, A. R. (Arthur Roland), 1843-1912 and Larken, Arthur Staunton, d. 1889. Lincolnshire Pedigrees. Google Books, accessed January 2019.”

- “More Emigrants in Bondage 1614-1775.” Ancestry.com, accessed January 2019.

- “Provincial Court Land Records, 1699-1707.” Maryland State Archives.

- “British Roots of Maryland Families, Vol 2.” Ancestry.com, accessed January 2019.

- “The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database, Voyage 9863 (Speedwell) 1868.” Slavevoyages.org, accessed January 2019.

- “They Knew They Were Pilgrims,” Chapter 1. Erenow.com, accessed January 2019.

- “Lawful to Set to Sea,” Chapter 11. Erenow.com, accessed January 2019.

- Hynson, Jerry M. Free African Americans of Maryland 1832. Heritage Books, 2007.

- Donnan, Elizabeth, ed. Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to the Americas, vol. III. Washington, DC, 1930.

- “Maryland State Colonization Society.” Wikipedia, accessed January 2019.

- “Goodhand Family Book.” Ancestry.com, accessed January 2019.

- “US Federal Slave Schedule, Christopher Goodhand, 1850.”

- “Will of Christopher Goodhand, 1857.” Maryland State Archives.

- “US Census, Maryland, Queen Anne’s County, 1850, and 1860.” Ancestry.com, accessed January 2019.

- “U.S., Civil War Draft Registrations Records, 1863-1865.” Ancestry.com, accessed January 2019.

- Stong, J. G. Map of Queen Anne’s County, 1866, District 1. Legacy of Slavery in Maryland, Maryland State Archives.

- “Manumission of Levi Chase.” Queen Anne’s County Land Records, Maryland State Archives.

- “Civil War Soldiers, Union, Colored Troops 56th – 138th Infantry.” Fold3.com, accessed January 2019.

- “Journal of the Proceedings of the Maryland State Senate, Table 21.” Google Books, accessed January 2019.

- “Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the United States Colored Troops: Infantry Organizations, 36th through 40th, Levi Chase.” National Archives.

- “Battle of the Crater.” Wikipedia, accessed January 2019.

- “Deed between Susan Goodhand, Emory Chase, et al.” Queen Anne’s County Land Records, Maryland State Archives.

- “Deed between J. Morhling Sudler, Emory Chase, James Milbourne, Trustees, et al.” Queen Anne’s County Land Records, Maryland State Archives.

- “Tombstones of Queen Anne’s County, Vol 3.” Upper Shore Genealogical Society.

- “Will of Asbury Johnson, 1866.” Maryland State Archives.

- “Certificate of Freedom, Asbury Johnson, Albert Johnson, 1857.” Maryland State Archives.