Written Apart

Where did Asbury Johnson, my 3rd great grandfather, a free black on Maryland’s Eastern

Group 1: Johnson, page 115

Males (as listed in order)

- Aaron Johnson, 30

- Philip Johnson, 45

- Asbury Johnson, 9

- Alfred Johnson, 5

- James Johnson, 23

- Nat Johnson, 49

Unfortunately, this part of the census is separated into male and female groups (other counties are not). It is possible however to identify families by matching listed associates with each male and female family group to build a preponderance of evidence to recombine the family units.

I found separated several male and female Johnson groups and then matched most of them by examining the surnames before and after each group, and the order of listing. So for example, if one male group had Gould, Comegys and Little surnames surrounding it, and one female group had the surnames, and they were in the same order of appearance in the list Johnson male group 5, Johnson female group 5, I could reconnect families. In my case, matching surnames included Massey, Anderson, Warwick, Faulkner, and Blake. In this way, I identified the correct Johnson female group linked to Asbury’s family. The female group is as follows:

Group 2: Johnson, page 126

Females (as listed in order)

- Jenny Johnson, 52

- Hester Johnson, 20

- Sarah Johnson, 2

- Charlotte Johnson, 26

- Netta Willamson, 90 (possible mother/grandmother to Charlotte or Hester)

- Adeline Johnson, 2 Ana Maria Johnson, 2 (twins)

It’s incredibly exciting to have reunited the family and it will give me countless new leads to follow. Furthermore, revisiting the census leads me to new conclusions about Asbury’s lineage. I’ve deduced that Aaron is probably Asbury Johnson and Alfred Johnson’s father based on their proximity in the census. A second clue lay in the fact that Asbury is a wealthy landowner in 1860 as documented on that census. Where did he get the money to buy a farm? How did he build his wealth? Did he have a headstart?

Land in the Family

A thorough review of Queen Anne’s County land records from 1707 – 1851 (MSA CE 144 – 145) reveals no sales of lands to Asbury Johnson, my 3rd great grandfather. D

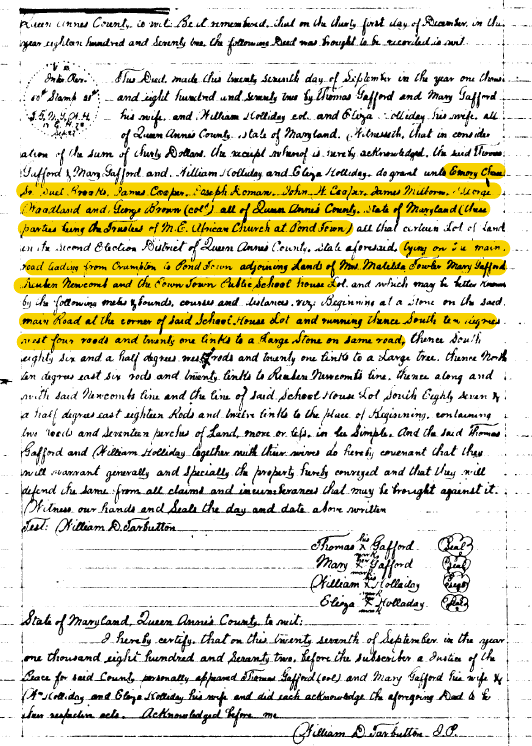

Transcription:

“Queen Anne’s County, to wit. Be it remembered that on the Sixth day of

I’ve thoroughly researched every transaction (deed, bill of sale, manumission) made by James Browne and found only one sale of land to a free negro, Aaron Johnson. Browne was a wealthy planter. The 1810 census shows he owned 5 slaves, and the 1820 census shows Browne owned 4 slaves at that time

Comegys Reserve first appears named in the will of Andrew Cornelius who died in 1796. He left the land to his son Andrew Cornelius Jr. It’s unclear when Andrew Cornelius gained his tract on Comegys Reserve, however, sources suggest that William Comegys III (of Kent Island) gave his brother Isaac Comegys land in Queen Anne’s County called “Comegys Reserve” containing 103 acres. The Comegys were Swedes from the Swedish colony in Delaware who became planters in Kent County and Queen Anne’s County in the mid-1700s. On 16 Jan 1765, Isaac Comegys sold the reserve to Joseph Ireland. Its likely Ireland (a Calvert County native) sold the land to James Brown so the chain of ownership would look like the following:

William Comegys III (103 acres) > Isaac Comegys (103 acres) > 1765 Joseph Ireland > James Brown OR Hannah Spry (wife) > 1829 Aaron Johnson ( 6 Acres)

To my son Daniel Cornelius, all those parts of two tracts of land in Queen Anne’s County upon which I now live the one called Comegy’s Reserve, the other Gunthers Lot; except the part of Comegys Reserve which is hereafter devised by me to my son Andrew Cornelius. In case my son Daniel shall die without lawful issue of his body, then the sd. to my son Nicholas Cornelius.

To my son Andrew Cornelius all that tract of land called The Pearl lying in Queen Ann’s Co. containing one hundred a. of land, also sixty a. of my xxx. part of the tract of land called Comegys Reserve (being the part excepted in the above devise

to my son Daniel), to be laid off for my son Andrew so as to include the north end of the part of the sd. tract now held by me and adjoining the one hundred a. of land called the Pearl. In case my son Andrew shall die without lawful issue of his body, then I give the sd. part of the tract of land called The Pearl and also that part of Comegys Reserve to my son Joseph Cornelius.To my son Andrew Cornelius two Negro men: Cesar (and) Robert.

To my son Daniel Cornelius one Negro boy James, Negro girl Margaret.

To my son Joseph Cornelius Negro girl Rachael and two Negro children Temperance (and) William.

To my dau. Mary Cornelius Negro boy Richard.

To my dau. Rebecca Cornelius Negro boy Jacob.

To my dau. Elizabeth Cornelius Negro girl Esther.The residue of my personal estate to my sons: John, Daniel, Nicholas, Andrew & Joseph & to my daus. Mary, Rebecca & Elizabeth – equally divided between them. I appoint my son Daniel Cornelius sole executor.

Will of Andrew Cornelius 1796

Logically, I wondered if Aaron Johnson or his parents were formerly enslaved by either the Cornelius, or Brown, or Spry family. An examination of land records, bills of sale, and manumissions reveal some incredible and sometimes heart-wrenching facts about these family’s business transactions.

First, Andrew Cornelius’ son, Daniel Cornelius – sole executor of his estate, lead his siblings, Mary, Elizabeth, and Andrew Jr. to the courthouse in 1796 right after their father’s death. There they freed the Cornelius enslaved willed to them by their father. The remarkable manumission lists the following enslaved and the date they were to be freed; Robert 1803, Richard 1805, Jacob 1808, Esther 1805, Margaret 1808, James 1808. Witnesses inclu Thomas Roberts and Samuel Cook.

Joseph Cornelius, another son of Andrew and who received 3 enslaved in the will, did not participate in the mass manumission of the “sundry negros.” There was no clear record connecting Aaron or his presumed father Phillip to the Cornelius family.

Records show James Browne, who sold the land to Aaron, made 3 sales of his enslaved in 1816. His first sale was South to feed the beast that was King Cotton. Browne sold Sophia, age 15, to a slave trader in South Carolina. He then sold 9 of his enslaved to Edward Brown (presumably his brother) Hannah -34, Ned -21, Nance -7, Margaret -4, Bill -9 mos (son of Hannah), Noah -19, Doll -21, Beck -17 with male child 8 yrs. The last sale was of a girl -11, Ellen, to Stephen Wycoff of the county. Clearly, Browne was fully utilizing of enslaved labor, and willing to participate fully as a trader and purchaser of enslaved labor to his benefit.

Given that Browne was embroiled in the business of enslaved labor, perhaps it was his wife Hannah Spry that instigated and approved of the eventual sale of Browne’s portion of Comegys Preserve to a free negro Aaron Johnson? After all, records show that while she was married to her first husband Samuel Spry, the family sold a portion of their land on Guyders Range to another free negro by the name of James Price. Or perhaps for Browne, it was just business.

Maryland was a tobacco-growing state throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Cultivating tobacco was labor-intensive and depleted the land fast. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Maryland planters shifted to wheat and other crops. They needed less labor for these less-intensive crops and started selling their enslaved south or freeing them to save money. This could have been a factor in the Cornelius family’s mass manumission as well.

Clearly, the source of Asbury’s ability to build a prosperous free family and farm thirty years before emancipation came from his father’s ability to purchase those first 6 acres of land. Make no mistake, this was a mighty act of self-sufficiency in 1829 for a free black. I can only imagine how Aaron, his wife, and their children must have felt at the end of the exchange of those $54 hard-earned dollars.

So while there are no other clues about Aaron’s lineage in the Brown and Spry records, one tantalizing clue appears in the 1850 census. Living immediately next door to Asbury Johnson and his family are William Cornelius and family, descendants of Andrew Cornelius. Furthermore, I’ve now identified the Cooper brothers family. Recall the Cooper brothers also received a Certificate of Freedom witnessed by Col. Lemuel Roberts in 1857 on the same day as Alfred and Asbury Johnson. One Michael Cooper was listed as living on land in the will and probate of Christopher Goodhand. Michael and his family including sons James and John Cooper are found in the 1850 census. Perhaps the Coopers and Johnson family were related? And in Andrew Cornelius will, I find one Cesar (negro man) left to Andrew Jr. A free black man Cesar Faulker also appears in the 1832 census. Could the Faulkners be related to the Johnson clan? Separately, a Cesar Johnson (free negro) appears to have purchased on Kent Island in QAC from one Thomas Lynch in 1822 (QAC Land deeds TM No. 3 page 331). Could Cesar Johnson be the same Cesar enslaved by Andrew Cornelius and willed to Andrew Jr?

Together Again

The search continues to identify who freed the Johnson family among the dusty digitized records of Queen Anne’s County. My reconstituted and combined Johnson family group of the 1832 census is now as follows:

Philip Johnson, 45 married Jenny Johnson, 52

- Aaron Johnson, 30

- James Johnson, 23

Aaron Johnson, 30 married Charlotte Johnson, 26

- Asbury Johnson, 9

- Alfred Johnson, 5

- Adeline Johnson, 2 (twin)

- Anna Maria Johnson, 2 (twin)

James Johnson 23 married Hester Johnson 20?

- Sarah Johnson, 2

With this construction, I reclaim the women ancestors whom I thought lost to time, including my 4th great-grandmother Charlotte, and 5th great-grandmother Jenny. I say your names.

By the 1840 census, the Browne and the Johnson family are still neighbors. Phill Johnson is listed as the head of household. There 6 in the household, 1 male under 10 (born btw 1830-1840), 2 males between 10 –

I can see these early Johnsons in my mind’s eye walking their fields at dusk on a cold crisp January evening, the winter sun setting behind the trees and over the fallow fields. I envisage Aaron holding Charlotte’s hand as

In a world that guaranteed their people absolutely nothing, not even the dignity of familial bonds, they’d survived, they’d lived and thrived. And now this land, impossibly, incredibly, was theirs. They would choose when to rise and till the land. They would choose where to build the homestead. They would choose what crops to plant, which animals to raise. They would choose were to plant the well. They would choose which parcel of their six acres to set aside for the family cemetery. They would choose whom to hire, if need be, to help them work their own corner of Comegys Reserve.

Sources.

- “US Census, Maryland, Queen Anne’s County, 1810, 1820, 1850, and 1860.”

- Hynson, Jerry M. Free African Americans of Maryland 1832. Heritage Books, 2007.

- Will of Asbury Johnson, 1866. Maryland State Archives.

- Deed of Aaron Johnson, QAC Deed Books, T.M. No. 5 page 222. Familysearch.org, accessed December 2018.

- Will of Andrew Cornelius, Queen Anne’s Co., MD, W.H.N. No. 3. Familysearch.org, accessed December 2018.

- Bill of Sale, James Browne to George Lake, QAC Deed Books, T. M. No. 1 page 228. Familysearch.org, accessed December 2018.

- Bill of Sale, James Browne to Edward Browne, QAC Deed Books, T. M. No. 1 page 233. Familysearch.org, accessed December 2018.

- Bill of Sale, James Browne to Stephen W. Wickoff, QAC Deed Books, T. M. No. 1 page 236. Familysearch.org, accessed December 2018.

- Deed, Samuel Spry to James Price, QAC Deed Books, T. M. No. 3 page 415. Familysearch.org, accessed December 2018.

- Brown, June D. Cecil County, Maryland Land Records, Abstracts. Willow Bend Books, 1999.

- Queen Anne’s County MD Land Records, Liber RT G folio 194.

- Moss, Ernestine Parke. Cornelius Comegys of Kent County, Maryland. Published by the Author, 1982.

- Skinner, Vernon L Jr. Abstracts of the Prerogative Court of Maryland 1674-1774. Family Archive CD number 206. Broderbund, 1998.